Every so often, be it in game code or in an editor extension you will need to traverse the scene or a part of the scene to perform processing on game objects.

In this article I demonstrate a variety of techniques for scene traversal in Unity. Later I'll show how you might make practical use of these techniques. Towards the end I'll introduce my open-source scene traversal library which wraps up and normalises many of these techniques in a friendly API.

Along the way we'll learn some computer science: tree traversal and recursion. We'll also learn about LINQ, which can really help processing and transformation of collections.

Contents

Table of Contents generated with DocToc

- My setup

- Example code

- Why is scene traversal useful?

- Scene traversal with the Unity API

- Sub-tree traversal

- The dangers of recursion

- Scene traversal with the Scene Query API

- Realistic examples

- Conclusion

My setup

I am currently using Unity 5.3.4 and Visual Studio Community 2015.

Example code

You can find an example Unity project with the code on github:

https://github.com/Real-Serious-Games/Unity-Scene-Traversal-Examples

Please download the Unity project to follow along with the examples that are coming up.

Why is scene traversal useful?

So why would you want to do scene traversal? Unity scene traversal is really just tree traversal, but performed on the Unity hierarchy.

Tree traversal is a technique often used in computer science and computer programming. A tree is a fairly common data structure and has many applications. Searching is one common use case.

Another very relevant use case: trees are commonly used for spatial partitioning in almost every 3D game. Trees are also often used (under the hood) to implement dictionaries and hash tables. There are many reasons why the tree data structure is a fundamental and pivotal data structure in software development.

So the Unity hierarchy is a tree. Why would we want to traverse it specifically?

Here are some example use cases:

- Walk a sub-tree of the hierarchy and add components.

- Walk a sub-tree and change the color of materials (maybe to indicate selection?).

- Walk a sub-tree and merge meshes (for optimization).

- Finding the common parent or root of two or more game objects in the scene.

We'll explore some of these examples after covering the basics.

Tree traversal is also very useful in more complex use-cases. Scene-based dependency injection is one such use case, but I'm saving that for a future article. Automating processes for scene management is another.

Scene traversal with the Unity API

Let's work through some basic examples of scene traversal using the Unity API. All of the numbered sections below have working examples on github. Please download the Unity project so you can follow along.

1. Enumerate all game objects

This most basic example shows how to enumerate all game objects in the scene:

GameObject[] allGameObjects = GameObject.FindObjectsOfType<GameObject>();

foreach (var gameObject in allGameObjects)

{

// ... Do something with the game object ...

Debug.Log(gameObject.name);

}

This code traverses all game objects but it has zero knowledge of the tree structure of the scene. That is to say that it doesn't understand the parent-child relationships that exist between game objects.

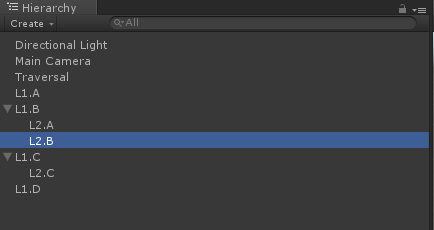

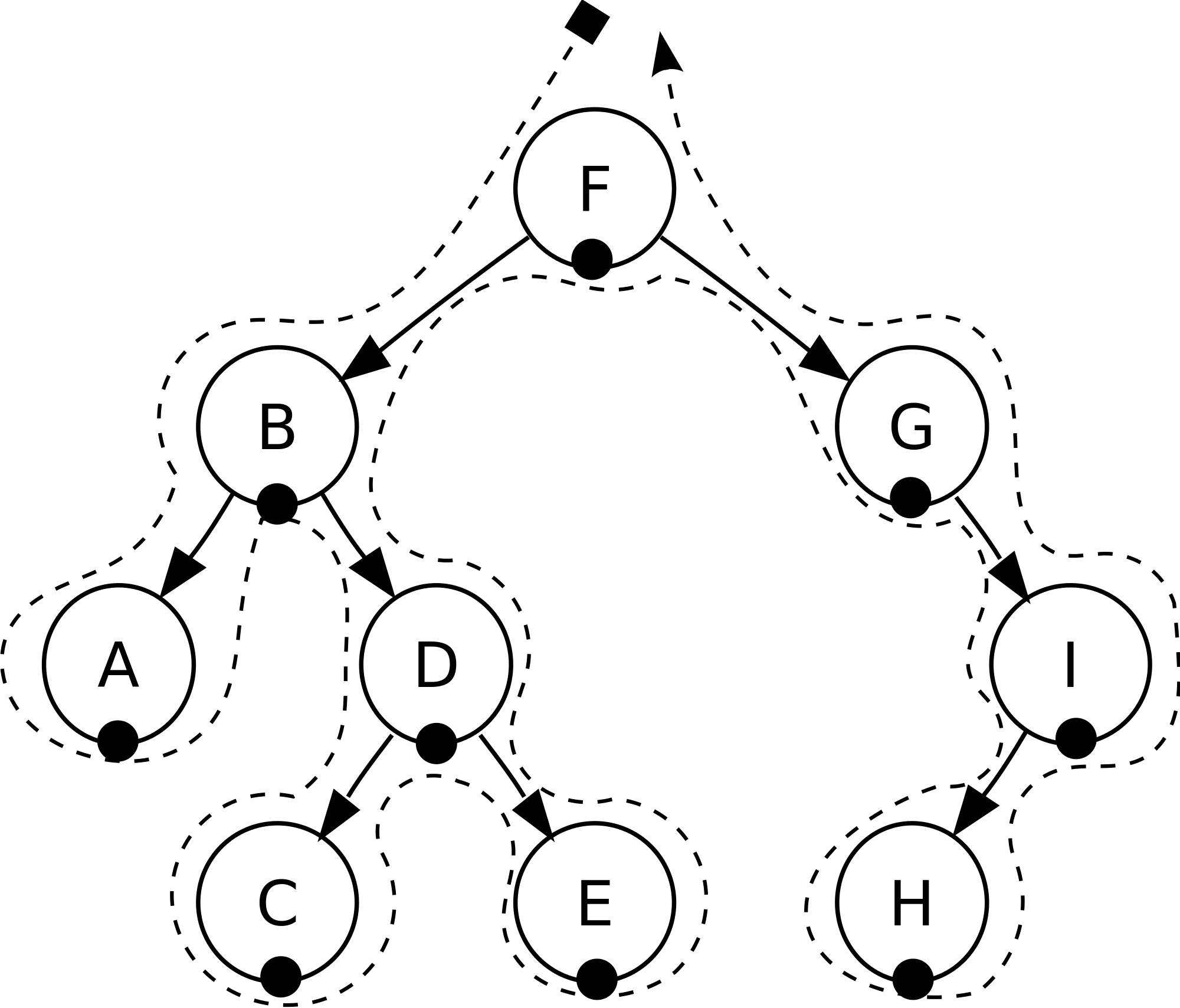

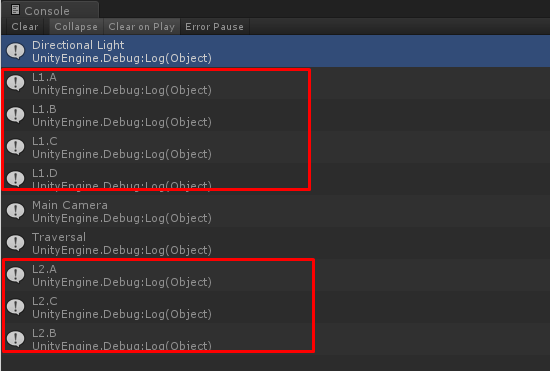

The following image shows the example hierarchy:

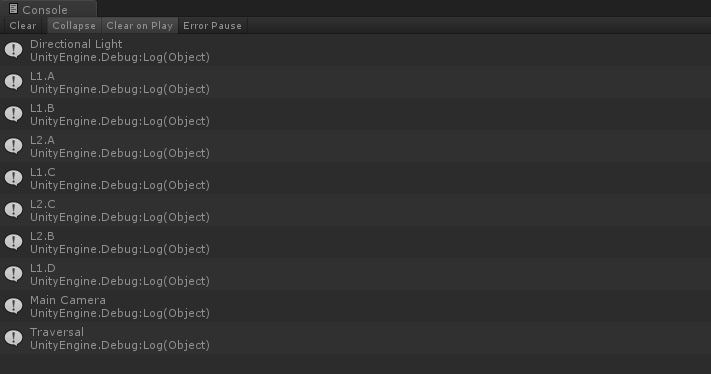

This is the output when we Play in the Unity Editor:

2. Identify root nodes

To perform a recursive traversal of the scene we must first identify the root nodes of the scene. That is those game objects that have no parent because they are at the top of the hierarchy.

Since Unity v5.3 this is much easier than it used to be, you can now use SceneManager and call GetRootGameObjects:

var rootObjects = SceneManager.GetActiveScene().GetRootGameObjects();

foreach (var gameObject in rootObjects)

{

Debug.Log(gameObject.name);

}

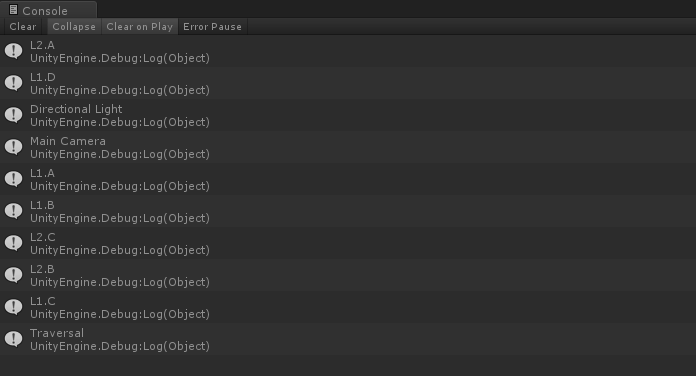

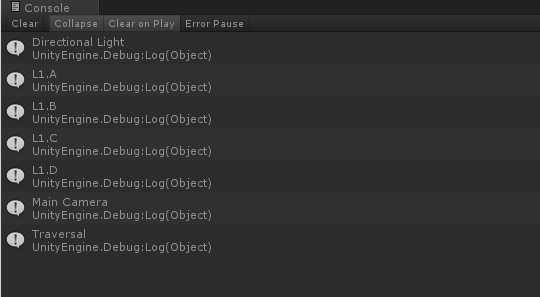

For this example the hierarchy is setup as before. Note in the output however that only the level 1 game objects are listed:

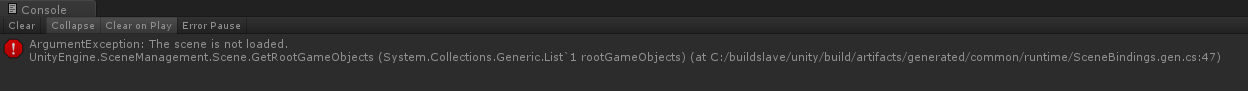

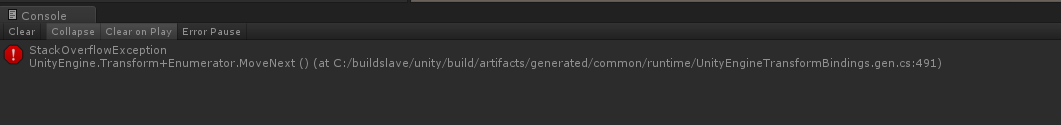

Unfortunately there are problems with this in Unity 5.3.4f1. You can run this code in Start or Update but you can't run it in Awake. Apparently this will be fixed in a future version of Unity. At the moment when I try to execute this code in Awake I see the following error:

If you are on an older version of Unity then there is no direct way to find root game objects. Instead we must traverse all game objects and find the ones that have no parent:

GameObject[] allGameObjects = GameObject.FindObjectsOfType<GameObject>();

foreach (var gameObject in allGameObjects)

{

if (gameObject.transform.parent == null)

{

// ... Do something with the root game object ...

Debug.Log(gameObject.name);

}

}

This is an expensive way to find root game objects, yet this is what you must do for older versions of Unity to identify root nodes in the scene. I'm not sure why there wasn't a convenient and performant means to identify root nodes prior to Unity 4.5.3, arguably something that should be in version 1 of any game engine that has a scene.

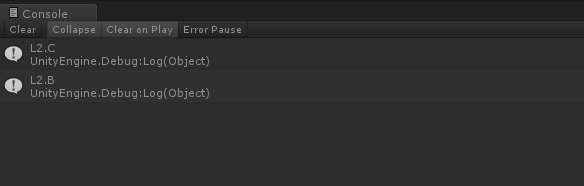

3. Access children

To traverse the entire scene we must be able to access the children of a game object.

This example enumerates the children of a particular game object:

GameObject parentGameObject = ... some game object ...

foreach (Transform childTransform in parentGameObject.transform)

{

var childGameObject = childTransform.gameObject;

// ... Do something with the child gameobject ...

Debug.Log(childGameObject.name);

}

Here is the output:

You can see that only the children of the L1.B game object have been displayed.

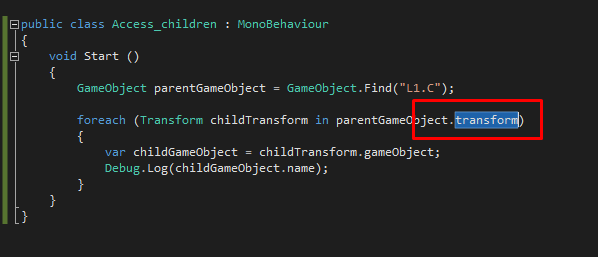

Notes about Transform and IEnumerable

In the previous example I used foreach to iterate the Unity Transform object. This is possible because Transform implements the IEnumerable interface that is required by foreach.

You can check this yourself. In Visual Studio select the transform property:

Now hit the F12 key. I'm assuming you have the same default keybindings as I do (if not you can right click and Go To Definition).

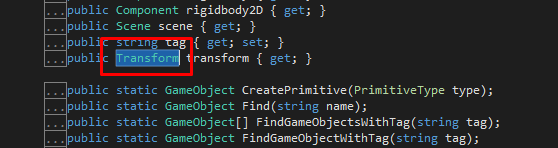

The F12 key takes you to the definition. This is an extremely useful feature of Visual Studio. This takes you to the transform declaration in GameObject:

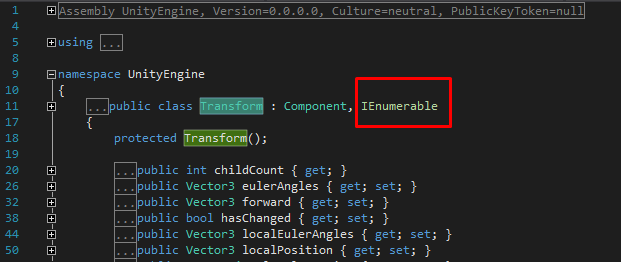

Now select the Transform type name and hit F12 again. You have followed the chain of declarations and you can now see for yourself that Transform implements the IEnumerable interface:

Note in the foreach loop that we explicitly typed the iterator as a Transform. Previously we have been using the var keyword. With the var keyword the iterator is implicitly typed. For this example we used the explicit type because Transform implements the non-generic version of IEnumerator. That is to say that C# sees a Transform as a collection of Objects and not as a sequence of transforms. If Unity had implemented the generic IEnumerator<Transform> instead of the non-generic IEnumerator then we wouldn't need the explicit typing.

Depth first

Now we can start to put things together. We have the ability to identify root nodes. From the root nodes we can enumerate children. From the children we can enumerate the grand-children and so on to the depths of the hierarchy.

We will code this using recursion. Wikipedia makes this seem more complicated than it really is. For my purposes recursion simply means that we have one function that calls itself. Why does it call itself? The reason was stated in the previous paragraph. We must enumerate the children, then the children of the children, the children of the children of the children and so on and so on. To implement this we need a function that enumerates the children of particular game object and then calls itself for each child game object. This is recursion.

We are looking at depth-first traversal first because I think it is the most intuitive, useful and easy to understand tree traversal technique.

4. Pre-order traversal

The first type of depth-first traversal is called pre-order. It is called pre-order because you visit the parent node before visiting the children:

Depth-first traversal (pre-order):

Thanks to Wikipedia for the image

We can implement it like this:

void PreOrderTraversal(GameObject parentGameObject)

{

// ... Do something with the parent before the children ...

Debug.Log(parentGameObject.name);

foreach (Transform childTransform in parentGameObject.transform)

{

var childGameObject = childTransform.gameObject;

PreOrderTraversal(childGameObject); // Recursion!

}

}

To initiate traversal call the function on each root game object:

foreach (var rootGameObject in SceneManager.GetActiveScene().GetRootGameObjects())

{

PreOrderTraversal(rootGameObject);

}

In the output of this example you will see game objects displayed in order with parents before children:

5. Post-order traversal

Post-order traversal is the opposite to pre-order. It visits the parent node after visiting the children:

void PostOrderTraversal(GameObject parentGameObject)

{

foreach (Transform childTransform in parentGameObject.transform)

{

var childGameObject = childTransform.gameObject;

PostOrderTraversal(childGameObject); // Recursion!

}

// ... Do something with the parent after the children ...

Debug.Log(parentGameObject.name);

}

To initiate the traversal:

foreach (var rootGameObject in SceneManager.GetActiveScene().GetRootGameObjects())

{

PostOrderTraversal(rootGameObject);

}

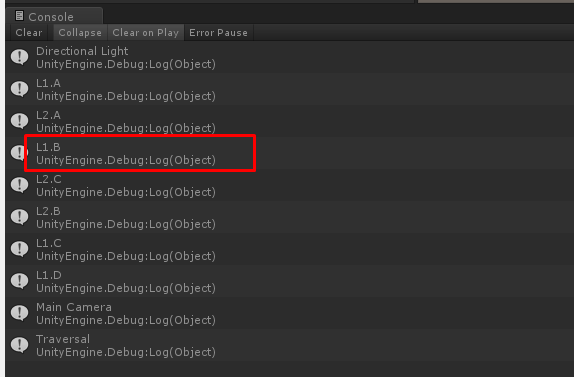

You'll notice in the output that the level 1 object L1.B is displayed in the console after it's level 2 children:

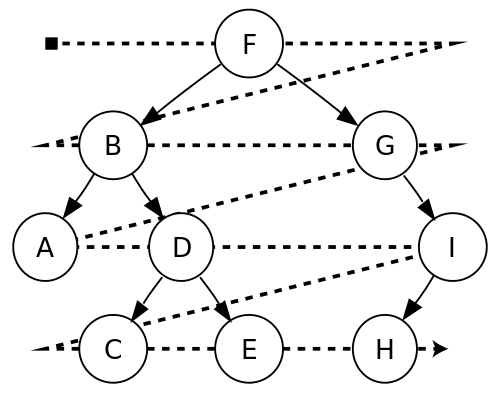

6. Breadth-first traversal

Breadth-first traversal is an alternative traversal technique to depth-first. Instead of deep-diving into the tree it visits each level before drilling down to the next.

Breadth-first traversal:

Thanks to Wikipedia for the image

To use breadth-first we first need a convenient way to retrieve all children for an entire hierarchy level.

Here's a first pass at it:

IEnumerable<GameObject> GetChildren(IEnumerable<GameObject> hierarchyLevel)

{

var children = new List<GameObject>();

foreach (var parentGameObject in hierarchyLevel)

{

foreach (Transform childTransform in parentGameObject.transform)

{

var childGameObject = childTransform.gameObject;

children.Add(childGameObject);

}

}

return children;

}

Note that we have two loops here. The outer loop enumerates the current level of the hierarchy. The inner loop iterates the children of each game object at this level.

We can use LINQ to avoid explicitly baking the children list:

IEnumerable<GameObject> GetChildren(IEnumerable<GameObject> hierarchyLevel)

{

foreach (var parentGameObject in hierarchyLevel)

{

foreach (Transform childTransform in parentGameObject.transform)

{

var childGameObject = childTransform.gameObject;

yield return childGameObject;

}

}

}

The combination of IEnumerable return type and the yield statement is what makes this code LINQ. These are the C# language features that power LINQ. Note that I prefer LINQ's method syntax over its query syntax.

Now that we can get all children at each hierarchy level we can implement a recursive breadth-first traversal function:

void BreadthFirstTraversal(IEnumerable<GameObject> hierarchyLevel)

{

foreach (var gameObject in hierarchyLevel)

{

// ... Do something with the game object ...

Debug.Log(gameObject.name);

}

BreathFirstTraversal(GetChildren(hierarchyLevel)); // Recursion!

}

To initiate the traversal:

void BreadthFirstTraversal()

{

BreadthFirstTraversal(

SceneManager.GetActiveScene().GetRootGameObjects()

);

}

Looking at the output you can see that all the level 2 game objects are displayed after the level 1 game objects:

Sub-tree traversal

So far we have examined recursive traversal functions that operate on the entire scene. Often however we simply want to traverse a sub-tree in the hierarchy. This is easily achieved with the PostOrderTraversal and PreOrderTraversal functions as both of these are able to start the traversal with whatever game object you want.

BreadthFirstTraversal is a little different. It takes a collection of game objects rather than a single game object. However with the addition of a simple helper function we can adapt breadth-first traversal to work with a sub-tree:

void BreathFirstTraversal(GameObject parentGameObject)

{

BreadthFirstTraversal(new GameObject[] { parentGameObject });

}

Note that we are overloading BreathFirstTraversal to take a single game object as its parameter. The overloaded function simply repackages the single object in an array and passes it into the original version of the function.

Descendants

Sometimes it useful to simply find a collection of all the descendants of a particular game object. By descendents I mean the children, grand-children and so on.

This can easily be done using LINQ:

IEnumerable<GameObject> FindDescendents(GameObject parentGameObject)

{

foreach (var childTransform in parentGameObject.transform)

{

var childGameObject = childTransform.gameObject;

yield return childGameObject;

foreach (var descendent in FindDescendents(childGameObject))

{

yield return childGameObject;

}

}

}

Note that this has the effect of flattening the sub-tree to a simple collection.

That particular example has the collection of games objects in pre-order, although it's trivial to convert to post-order if that's what you need.

If you don't like using LINQ for this sort of thing, then it's easy to convert it to a function that explicitly bakes and returns a list.

Ancestors

It's also useful to find the ancestors of a particular game object. By ancestors I mean the parent, the grand-parent and so on up to the root game object:

IEnumerable<GameObject> FindAncestors(GameObject parentGameObject)

{

Transform ancestorTransform = parentGameObject.transform.parent;

while (ancestorTransform != null)

{

yield return ancestorTransform.gameObject;

ancestorTransform = ancestorTransform.parent;

}

}

Note that for this function we don't need recursion. We are simply finding parent after parent until we hit the root game object, so we are able to use a loop and avoid recursion.

The dangers of recursion

If you have spent anytime using recursion you will most certainly have encounted a stack overflow (and I'm not talking about the ubiquitous programming Q&A site which you will also have most certainly encountered).

If you encounter a stack overflow while Playing in the Unity Editor it will look like this:

Why does this happen?

Recursion is essentially a loop. A function calls itself again and again forming a loop. What happens when a loop doesn't end? What we get is an infinite loop. Of course you'd never do this on purpose, however it's quite easy to achieve by accident. Normally when we use loops in programming and we find a bug that causes an infinite loop it will cause our program to hang. The program will stop responding while it spins in the loop and eventually we'll have to manually kill the process. A run-away recursive loop responds a little differently and it will very quickly crash your program. To understand why this happens we need to delve deeper into how functions actually work.

Everytime a function is called, while the function is inflight, space is reserved on the call stack. A program has only a limited amount of stack available. What this means is that for any given program only a limited number of function calls can be inflight at any point in time. Usually you don't care about this because the size of the call stack is big enough to handle most scenarios. However, when we have a runaway recursive function call, with each new function call more space is reserved on the callstack and the total space available can be quickly exhausted.

So a stack overflow is what happens when a program exceeds the space reserved for its call stack. As an aside, it's interesting to note that some languages can deal with infinite recursion through a mechanism known as tail recursion. The best example I can think of for tail recursion is implemented by Lua, a language that has been quite popular for game development.

7. Scene traversal with the Scene Query API

In this section I overview part of my open-source Scene Query code library which wraps up some of the techniques I've discussed so far in this article. You can find the code for the Scene Query library on github.

The primary purpose of this library is actually

scene query

(as inferred by the name). What is scene query? Well it's a way to query the scene as though it were some sort of database. Another analogy is CSS (cascading style sheets) selectors in web development. What if you could query the Unity scene in a similar way to as to querying a HTML document with a CSS selector? This is the essence of scene query, but this article isn't about scene query, I'm saving that for another blog post. In this section of this article I'm going to focus on the scene traversal aspect of the Scene Query library.

Note that example number 7 in the Unity example project demonstrates numerous features of the scene traversal API using a cut-down copy of the Scene Query library.

Getting the code

To use this API copy the code from github and put it in your project.

Alternatively you can grab the package from NuGet. You should be able to drop the DLL into your Unity project and then have access to the API.

A stripped down version of the code (just scene traversal, scene query features have been removed) is available in the example Unity project that accompanies this article.

Why did I make this library?

I created this library mostly because scene query is incredibly useful. The code that implements the scene query relies on scene traversal. So as part of that library I wrapped up various useful Unity scene traversal techniques.

I like the fact that my API feels more unified than the native Unity API. It is normalised and easy to use. It works well with Visual Studio intellisense and code completion. The Unity API feels all over the place. It's feels chaotic. It seems to have evolved haphazzadly, rather than be planned out as an effective API. My higher-level scene traversal API smoothes over some of the inadequacies and annoying issues that come with the Unity API.

Not everyone will agree of course, take this API as you will. If you like the API and it helps you, then use it. If not, simply use the native Unity API, it makes little difference.

Root nodes

Retreiving root game objects:

var sceneTraversal = new SceneTraversal();

foreach (var gameObject in sceneTraversal.RootNodes())

{

Debug.Log(gameObject.name);

}

Game Object Extensions

The scene traversal API comes with a number of extension methods that attach functions to GameObject.

Please take note that in the following examples it looks like we are calling functions on GameObject, but if fact we are not. We are really calling extension methods that don't normally exist in the Unity API. The Scene Query API extends GameObject with new functionality. This is a very useful technique that you will definitely want to use when you create your own APIs.

Parent

Retrieving the parent of a game object:

GameObject someGameObject = ... some game object ...

GameObject parent = someGameObject.Parent();

Root

Retreiving the root game object:

GameObject someGameObject = ... some game object ...

GameObject root = someGameObject.Root();

Children

Enumerating the children of a game object:

GameObject parentGameObject = ... some game object ...

foreach (var childGameObject in parentGameObject.Children())

{

Debug.Log(childGameObject.name);

}

Depth first

Pre-order

Enumerating the scene in pre-order:

var sceneTraversal = new SceneTraversal();

foreach (var gameObject in sceneTraversal.PreOrderHierarchy())

{

Debug.Log(gameObject.name);

}

Enumerating a sub-tree in pre-order:

GameObject parentGameObject = ... some game object ...

foreach (var gameObject in parentGameObject.PreOrderHierarchy())

{

Debug.Log(gameObject.name);

}

Post-order

Enumerating the scene in post-order:

var sceneTraversal = new SceneTraversal();

foreach (var gameObject in sceneTraversal.PostOrderHierarchy())

{

Debug.Log(gameObject.name);

}

Enumerating a sub-tree in post-order:

GameObject parentGameObject = ... some game object ...

foreach (var gameObject in parentGameObject.PostOrderHierarchy())

{

Debug.Log(gameObject.name);

}

Breath first

Enumerating the scene breadth-first:

var sceneTraversal = new SceneTraversal();

foreach (var leafGameObject in sceneTraversal.BreadthFirst())

{

Debug.Log(leafGameObject.name);

}

Enumerating a sub-tree breadth-first:

GameObject parentGameObject = ... some game object ...

foreach (var leafGameObject in parentGameObject.BreadthFirst())

{

Debug.Log(leafGameObject.name);

}

Just get leaf nodes

Enumerating only the leaf nodes in the scene:

var sceneTraversal = new SceneTraversal();

foreach (var leafGameObject in sceneTraversal.HierarchyLeafNodes())

{

Debug.Log(leafGameObject.name);

}

Enumerating only the leaf nodes in a sub-tree:

GameObject parentGameObject = ... some game object ...

foreach (var leafGameObject in parentGameObject.HierarchyLeafNodes())

{

Debug.Log(leafGameObject.name);

}

Descendents

Enumerating descendents (children, grand-children, etc) of a particular game object:

GameObject parentGameObject = ... some game object ...

foreach (var descendentGameObject in parentGameObject.Descendents())

{

Debug.Log(descendentGameObject.name);

}

Ancestors

Enumerating ancestors (parent, grand-parent, etc) of a particular game object:

GameObject someGameObject = ... some game object ...

foreach (var ancestorGameObject in someGameObject.Ancestors())

{

Debug.Log(ancestorGameObject.name);

}

Realistic examples

Now it's time for some practical and realistic examples of how to use some of these techniques.

I don't have working examples for these, this is just to give you a taste of how you can make use of these scene traversal techniques. These all rely on my scene traversal API, although you can easily achieve similar results with the native Unity API.

Add a component to an entire sub-tree

GameObject someGameObject = ... some game object ...

foreach (var descendent in someGameObject.Descendants())

{

descendent.AddComponent<MyComponent>();

}

Find game objects in a sub-tree that have a particular naming convention

This is an example that uses LINQ Where to filter out game objects that confirm to a particular naming convention.

string wheelPrefix = "Wheel_";

GameObject vehicle = ... some vehicle object ...

var wheels = vehicle

.Descendents()

.Where(gameObject => gameObject.name.StartsWith(wheelPrefix));

foreach (var wheel in wheels)

{

// .. Do something with each wheel ...

}

Find game objects in a sub-tree that have a particular component

We can improve on the previous code if we can filter out game objects by type rather than naming convention. In this example we use LINQ Where to find game objects that have a Wheel component:

GameObject vehicle = ... some vehicle object ...

var wheels = vehicle

.Descendents()

.Where(gameObject => gameObject.GetComponent<Wheel>());

foreach (var wheel in wheels)

{

// .. Do something with each wheel ...

}

Find game objects that don't have a particular component

We can easily inverse the previous example and filter out all games objects that don't have a Wheel component:

GameObject vehicle = ... some vehicle object ...

var nonWheels = vehicle

.Descendents()

.Where(gameObject => gameObject.GetComponent<Wheel>() == null);

foreach (var nonWheel in nonWheels)

{

// .. Do something with each non-wheel ...

}

Modify selected materials in a sub-tree

This example changes materials on a sub-tree.

var someGameObject = ... some game object ...

var someMaterial = ... some material ...

foreach (var gameObject in someGameObject.Descendants())

{

gameObject.GetComponent<Renderer>().material = someMateral;

}

Find common root game objects

Say you have a collection of game objects and you want to identify the common set of root objects.

You could do something like this:

IEnumerable<GameObject> gameObjects = ... game objects ...

var rootObjects = gameObjects

.Select(gameObject => gameObject.RootObject());

That code transforms (using LINQ) a collection of game objects to a collection of root game objects.

That was simple, but it doesn't quite do what we want. For example if we have two or more game objects under the same root object then that root object will appear in our list two or more times.

This is simple to fix by adding LINQ Distinct into the call chain:

var rootObjects = gameObjects

.Select(gameObject => gameObject.RootObject())

.Distinct();

Now we have a list of root objects with duplicates removed. Hooray for LINQ.

Collapse hierarchy

The most interesting use I can think of for scene traversal is to collapse all meshes in a sub-tree into a single mesh. This technique is useful when you want to optimize a scene, merging meshes for less draw calls:

void CollapseHierarchy(GameObject parentGameObject, MeshBuilder meshBuilder)

{

meshBuilder.PushTransform(parentGameObject.transform);

meshBuilder.AddMeshes(parentGameObject);

foreach (var child in parentGameObject.Children())

{

CollapseHierarchy(child, meshBuilder);

}

meshBuilder.PopTransform();

}

This example uses a fictional MeshBuilder helper class that can accumulate transforms and meshes as we traverse the hierarchy.

Hopefully this provides a compelling example of how scene traversal can be useful.

Conclusion

In this article I have examined various examples for traversing the Unity scene. We looked at examples using the native Unity API and then some examples using my open-source Scene Query API.

Hopefully I have inspired you to learn about and use tree traversal algorithms.

As far as LINQ is concerned we have only just scratched the surface, there is so much more it can do. It is a very valuable tool to add to your toolbox.

Reviewers

Daniel Vicarel

Thanks again to Daniel who provided invaluable feedback on tihs article.

Anthony Wood

Anthony Wood is an indie game designer and programmer based in Brisbane, Australia. In 2010, he co-founded Screwtape Studios, which to date has released four mobile titles and is currently gearing up to release it's first PC/Console game, Damsel. Anthony is also currently working as a game design and programming lecturer at SAE QANTM's Brisbane campus.

Special Thanks

Thanks to Mark Handford for becoming my second sponsor on Patreon.